What are the chances?

At 21:00 on Thursday 22nd March 2018, the BBC aired Contagion: The BBC Four Pandemic – “a nationwide experiment to help plan for the next deadly flu pandemic, which could happen at any time.”1Programme outline archived here.

This ‘experiment’ made some glaring assumptions:

- no one is immune to the virus

- people infect each other with viruses2Yes, it’s an assumption. Repeated experiments have not conclusively proven viruses can be transmitted person-to-person. Test that yourself in your life history – ever spent time with someone who’s been diagnosed sick with a virus, been coughing and sneezing and yet not got sick yourself? Additionally there’s also the alternative view that what we describe as “viruses” are not simply external, potential invaders seeking to ‘hijack’ our cells, but might actually be something our cells already make for various purposes. Neurobiologist Jonathan Jay Couey sketched out this possibility in a recent stream.

- proximity to a carrier, for X amount of time, means you will definitely (a) contract that virus and (b) pass it on

- viruses retain their fidelity (do not change) as they replicate through thousands and millions of people over time oh, and…

- viral transmission patterns are already understood well enough to assume that combining a mobile app and a mathematical model is a valid way to replicate and further study and learn about those patterns. 3To put it another way, how were the results of this experiment going to be assessed as valid and usefully predictive off real life?

It also presented quite a number of concepts to the public:

- pandemics are inevitable

- people without viral symptoms can spread a virus

- spike proteins

- antibodies mean immunity

- super-spreaders

- school closures

- restricting people gathering

- stay-at-home

- vaccines are the only way out because antibiotics can’t treat viruses

- vaccines need to be made faster

- the numbers infected will be huge

- more testing and surveillance always help4A logical fallacy. and are essential for public health…

The UK Government then used the data for 2020

The BBC aired the programme again on Tuesday 11th February and Saturday 14th March, 2020. Which would have been around the time the data gathered and modeled for the programme were being used to inform the UK Governments COVID response.

But, imagine if you can…

… that none of the above applied.

Seriously.

Put all those things aside.

Then ask yourself this question.

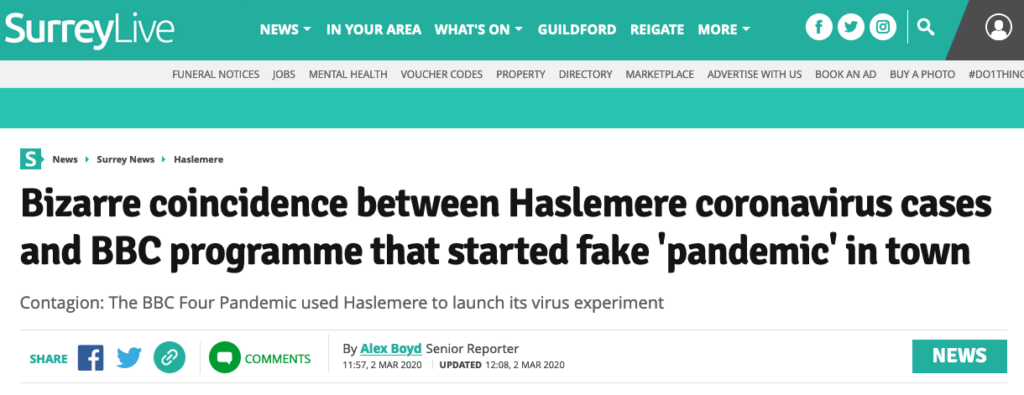

What are the chances that the very first instance of someone contracting COVID from someone else within the UK, just happened to occur in the very same town that the 2018 BBC programme had been set in: Haslemere?

Seriously.

Ask yourself…

… what are the chances?!

Because that IS what happened.

Pighooey lays it all out

In case you want to see the original

More BBC coincidences on Pighooey’s Substack and this 5-part playlist. | Related: Maths Team report5Archive. Copy of PDF (1.1MB)

- 1

- 2Yes, it’s an assumption. Repeated experiments have not conclusively proven viruses can be transmitted person-to-person. Test that yourself in your life history – ever spent time with someone who’s been diagnosed sick with a virus, been coughing and sneezing and yet not got sick yourself? Additionally there’s also the alternative view that what we describe as “viruses” are not simply external, potential invaders seeking to ‘hijack’ our cells, but might actually be something our cells already make for various purposes. Neurobiologist Jonathan Jay Couey sketched out this possibility in a recent stream.

- 3To put it another way, how were the results of this experiment going to be assessed as valid and usefully predictive off real life?

- 4A logical fallacy.

- 5Archive. Copy of PDF (1.1MB)